Climate change and El Niño have caused the worst mangrove die-off in recorded history, stretching along 700km of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, an expert says.

The mass die-off coincided with the world’s worst global coral bleaching event, as well as the worst bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef, in which almost a quarter of the coral was killed – something also caused by unusually warm water.

And last week it was revealed warm ocean temperatures had wiped out 100km of important kelp forests off the coast of Western Australia.

To assess the damage to the mangroves, Norm Duke, an expert in mangrove ecology from James Cook University, flew in a helicopter over 700km of coastline, where there had been reports of widespread mangrove die-offs.

He was “shocked” by what he saw. He calculated dead mangroves now covered a combined area of 7,000 hectares, as was first reported by the ABC on Sunday. That was the worst mangrove mass die-off seen anywhere in the world, he said.

“We have seen smaller instances of this kind of moisture stress before, but what is so unusual now is its extent, and that it occurred across the whole southern gulf in a single month.”

Knock-on effects

The devastated mangrove forests played an essential role in the region’s ecosystem, Duke said. They were nurseries for many fish species.

“But we also think of them as kidneys – as water filters and purifiers,” he said.

As water from rivers and floodplains runs into the ocean, mangroves filter a lot of sediment, and protect coral reefs and seagrass meadows. That service would be lost in the areas affected by die-off.

“There are already anecdotal reports of marine life dying and piles of dead seagrass washing up on the shore,” he said. “If that’s true, then turtles and dugongs will be starving in a few months.”

And it would get worse over the coming years as the roots of the dead plants rotted.

“The problem is the growth rate isn’t high enough to stabilise the environments,” Duke said. “In five or six years’ time, the roots will break down and those sediments will become destabilised. And that will threaten the near-shore habitats of seagrass and coral.”

The mangroves also protect the shoreline and coastal ecosystems from storms and tsunamis. Absorbing waves that hit the coast helps limit the impact of storms and rising sea levels.

“We need that resilience and protection of the shoreline so we can slow down the effects of sea level rise,” he said.

Death by global warming

Mangroves die off naturally on a small scale, but Duke had never seen anything of this magnitude.

Around the world there had been widespread destruction of mangroves, but usually as a result of direct local impacts such as clearing for the creation of shrimp farms, he said. But the areas in northern Australia were “relatively pristine”.

“So you can see global changes or influences more easily. Usually, local influences are far stronger.”

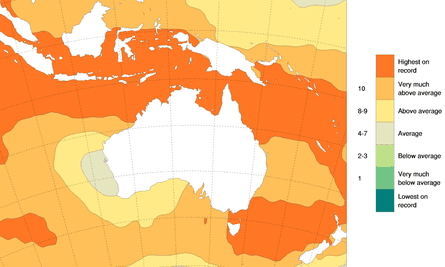

The clear culprit in this case was climate change, which was warming waters and making rainfall more erratic, Duke said. That put the mangrove forests at their tolerance limit, and when a strong El Niño hit the world this year – warming waters in northern Australia and drawing rainfall away – they were pushed past their tolerance thresholds.

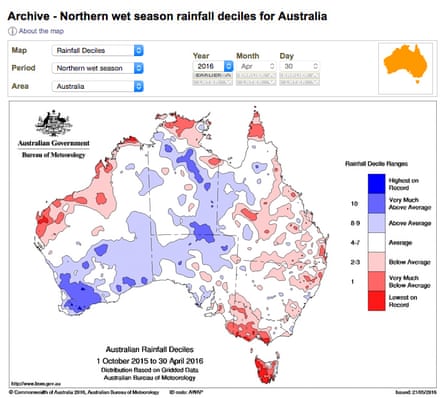

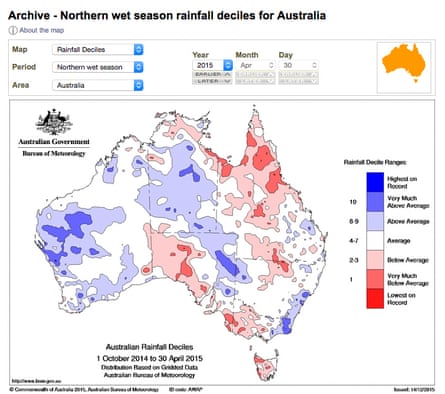

Greg Browning, from Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology, confirmed the past two years had seen unusually low rainfall and very high sea surface and air temperatures across the region where the die-off occurred.

“In a nutshell, there have been significantly below-average rainfall totals in the last two wet seasons ... and very warm sea surface temperatures,” he said. “When you have those departures from average conditions, it’s bound to affect the ecosystem in some way.”

The 2016 wet season was affected by the El Niño phenomenon, which produced dry conditions at the heart of the die-off. Browning said normally there were two or three bursts of monsoonal rains across the region, but in 2016 there was just one.

But the 2015 wet season, when there was no El Niño, was even drier.

This year, it is believed those dry conditions combined with a belt of record-warm sea surface temperatures across the north of Australia, as well as very warm air temperatures, to create a perfect storm that devastated the mangroves.

Browning said these conditions were a result of natural fluctuations, occurring on top of climate change. “[Global warming] exacerbates the situation,” he said. “It makes a bad situation much worse.”

Recovery and monitoring

Duke said mangroves were good at adapting, but not to such severe changes that occurred so quickly. How they would recover over the coming years was unclear.Some areas could transition completely away from being mangrove-dominated, and become salt pans – flat, unvegetated regions covered in salt and other minerals.

“Some zones have been completely removed of vegetation across the tidal profile,” he said. “The problem is that the rate of colonisation isn’t fast enough to stabilise those environments. So in five or six years’ time when the root material breaks down, the sediment becomes destabilised and no amount of seedling growth will stop the erosion.”

Duke said there had been very little monitoring of these relatively pristine mangroves in areas where very few people live. Such a program was urgently needed. “We need to be able to form a rapid assessment response for these emergent situations,” he said. “These habitats are on the retreat. They’re retreating far more rapidly than any of the endangered forests we have.

“We need to equip people to have independent assessments of what the local impacts are.”

Although they were among the most pristine mangroves in the world, they could be being affected by grazing.

“The question is how much of that is going on, and we need to be monitoring those sorts of influences so we can properly understand what are these larger effects, and are we reducing the resilience of mangroves so we are making them more vulnerable to the climate?”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion